On Saturday, January 11, 2025, we went to the invitational scrimmage hosted at the University of Vermont. Our team has collaborated with another southern Vermont team, Bennington’s Cookie Clickers, this year, but this invitational served as a good chance to get to collaborate with everybody, as we don’t get many opportunities to work with teams from northern Vermont. This year’s challenge is rather complex, and to our surprise we saw that many teams had similar solutions to the challenge. A frequent design that we saw — and the one that we chose for our robot — is a linear slide system to allow the robot to reach this year’s higher scoring bins. Despite many robots having a similar base idea, it was interesting to discuss the smaller differences between every robot. We saw, for example, a number of different claw designs and strategies for how to pick up game pieces. We discussed with different teams about how they designed their claws, and we found things we hadn’t even thought of such as having the claw aligned horizontally rather than vertically.

After we compared our designs, it was time for a round of judging! Many of us hadn’t experienced a judging session before, so it was a great practice for the new members. We discussed our process in designing the robot and our current hardware, as well as our intended strategies. We started the presentation with a strong overview of our different hardware mechanisms, featuring our linear slides, rack and pinion servo, and our wrist and claw mechanism. To follow up our hardware presentation, we discussed our developments in our robot’s software this year. This year, we started by integrating the PedroPathing algorithm for pathfinding, a departure from our previous strategy of writing everything ourselves. Later in the season, though, we found that PedroPathing’s (at that time) lack of a proper Gradle library, and our lack of proper knowledge of the internals, was holding us back. So, at the last minute, our software lead sat down and wrote a block-based pathfinding autonomous, combining ideas and routines from previous seasons, which worked brilliantly. In the presentation as a whole, something that we plan to improve is how we distribute the information presented between team members; some spoke too much, others not at all. Our presentation was decent overall, though, and we have definite targets for improving it.

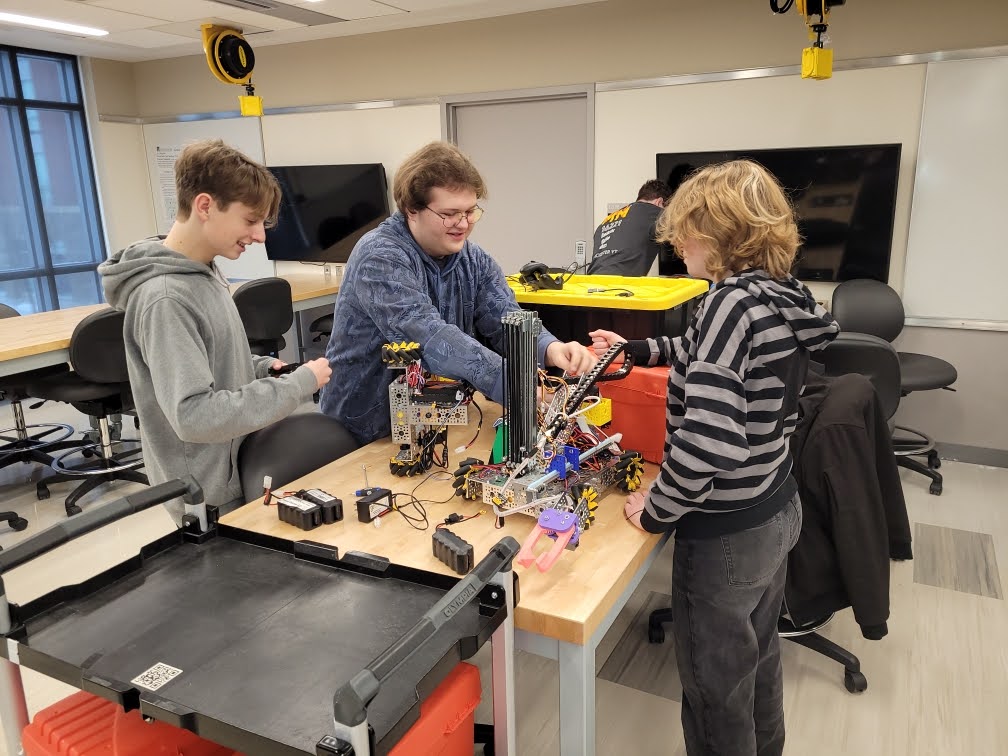

The last part of the invitational that we were able to attend was the practice matches, which led us to useful discoveries about our robot as well as potential game strategies. The scene was set: our robot waited, ready for action, on the full-sized playing mat, with the other teams standing ready. The suspense grew as the referee counted down the seconds to the moment of truth. Then, as the autonomous portion began, our robot was the only one that moved. We came to the realization that we were the only team with the foundations of a working autonomous. Our autonomous wasn’t anything too fancy yet, as it was just a simple parking mechanism we had recycled from a previous year, but nonetheless we managed to scrap it together for this season. The tele-op portion of the game, though, was a bit more interesting, as all teams had some sort of prepared tele-op system. Many different game strategies were used, but the main one that we saw was the usage of baskets. Our team designed our robot to be able to both score a basket and score specimens on the rungs of the submersible, so we were flexible with our scoring techniques. We tried a variety of different scoring methods, but we focused on getting better at hanging specimens, as the other teams wanted to prioritize basket scoring. We ran into a few technical problems, such as the traction of the claw not gripping pieces fully, though we hope to fix those in the coming days. The last part of the match struck and we raced over to the ascension zone, unrivaled again. In the final section of the game we discovered that we were the only team able to complete a level two ascent, which shocked us again as our ascension system used a similar design to many other teams’.

After some matches, we discussed claw designs with another team, along with the benefits of a horizontal claw versus our vertical claw. They showed us that they too had a vertical claw at one point, but got rid of it because after running some tests the horizontal claw proved to be more effective in sample collection. We hope to re-think our claw to make our collection easier. Since they were nice enough to help us out with our claw design, we helped them out with their difficulties with ascension. They also used a linear slide system to reach the higher collection bins, so we discussed how they could repurpose their slides as an ascension mechanism like we did. It was fun and constructive to provide feedback for each others’ robots, and, overall, we gained a lot of insight and ideas from our discussions. We hope to implement what we’ve learned as we continue to improve our robots, and to continue connecting with other teams to learn as much as we can. These collaborative events allow us to gauge our progress and improve our designs much more than we would be able to do otherwise. As such, we’d like to thank UVM for providing this incredible opportunity for all Vermont teams.

Overall, we are proud of where we are as a team and are on track to perform well in the state competition. We want to go as far as we can, and achieve the best we are capable of. We’re in a good place for this point in the season, and we hope to progress to regional competitions in Massachusetts again as we did last year.